Many students come to college thinking that “arguing” in an essay means to present a well- supported position. The definition of “argue” thus becomes a defense rather than an inquiry. In the real world, we're accustomed to "arguing" as trying to win. In college, "arguing" means to present a line of thought that takes into account different perspectives, additional evidence, and new ideas as it comes to a conclusion. In other words, a strong argument is one that incorporates both sides effectively.

Sophisticated thinkers and writers seek to advance and deepen the understanding via discussion; thus, at college we seek to encourage deeper discussions with the goal to have a richer and fuller understanding. To do this well, it’s important to go deeply into a subject rather than stay on the surface. While the approach of defending a position rather than exploring its layers may feel somewhat easier, there are only so many ways to learn from general subjects; we learn more, and find opportunities for growth and development more easily, when we narrow down the field of interest. As we work with an idea and consider it carefully, we continue to narrow it down, zeroing in on a particular angle or position that interests us and meets the needs of the assignment.

Identifying a position requires several steps:

-

First, understand the subject area from which the argument must come.

-

Second, break that subject area down into topics

-

Third, focus on developing a question whose answer can be identified and defended. As the subject undergoes continual narrowing and focusing, specific questions develop; the reasoned, detailed, careful answer to those questions becomes the argument.

-

Fourth, read, research, and discuss the potential answers to the question you’re asking so that your writing is multidimensional and well supported. The Guide’s chapter on “Using Your Resources” deals with this element of the process.

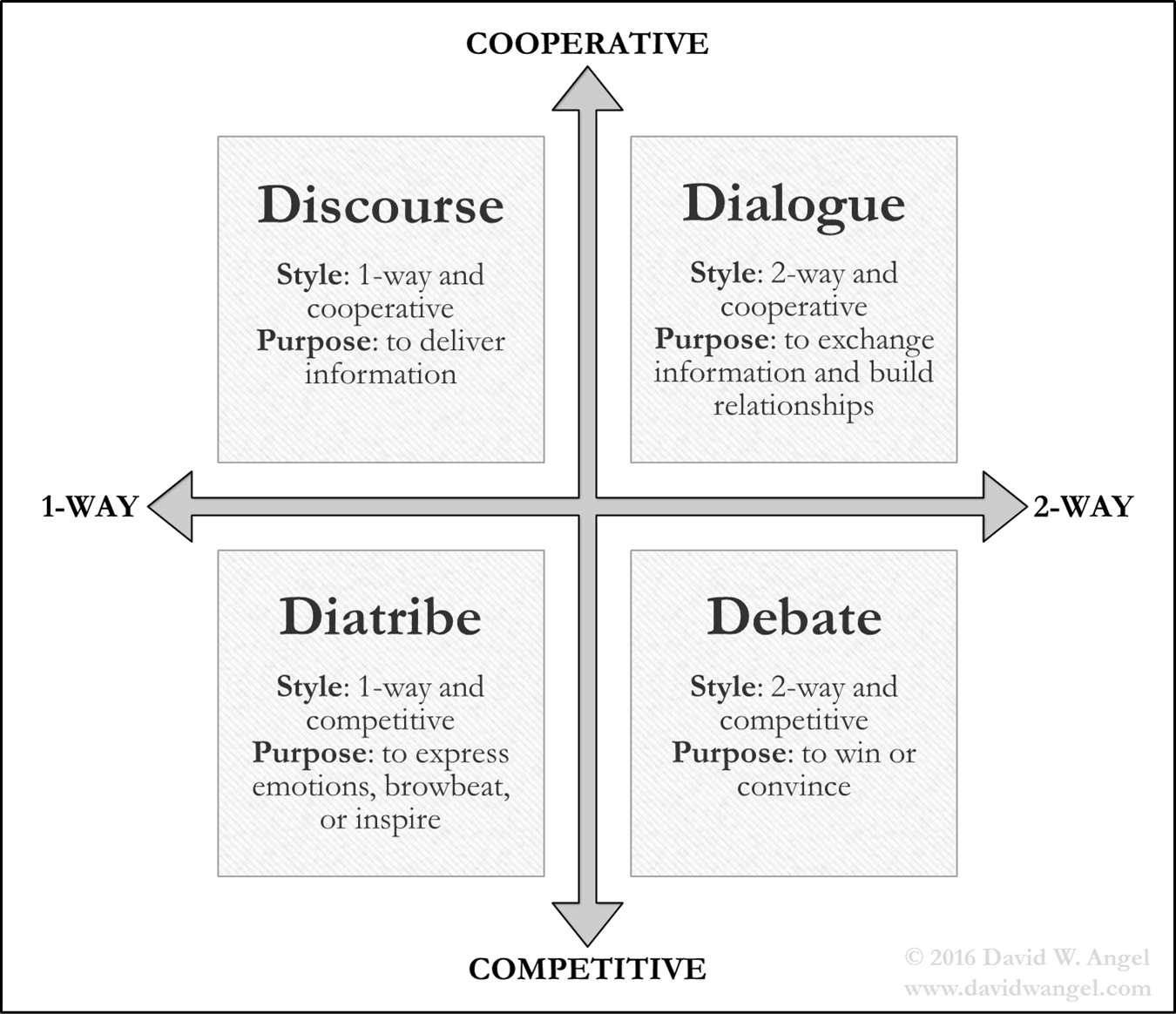

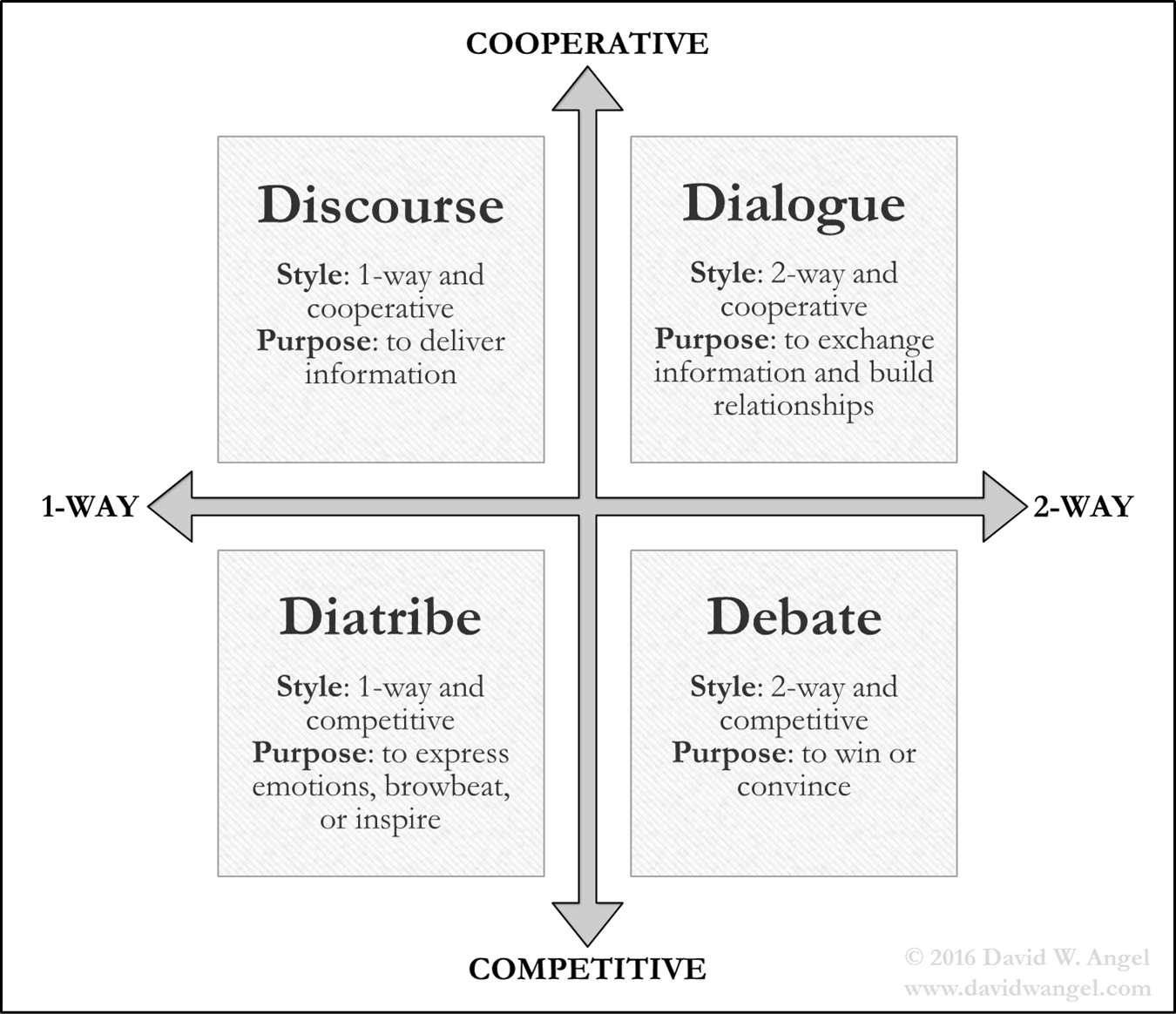

Remember: A true argument requires that other perspectives be taken into account, because once you have found a focus and can easily develop an opinion or come to a position on the questions that have been created, this can provide an opportunity for a discussion, exploration of different perspectives, and dialogue about values.

-

Opinion: statement of writer’s general attitude toward a specific subject, issue or event

-

Position: announcement of writer’s general attitude toward a specific subject, issue, or event, with explanation of reasons

-

Argument: statement that captures a spirit of debate and discussion about a specific topic, issue, or event

Not every writing assignment students get in their courses will be an argument essay. As mentioned earlier, students here write lab reports, correspondence, proposals, brochures, arguments, applications, evaluations, analyses, and host of others.

We also ask that students consider and evaluate questions and ideas, formulate their own responses to those ideas, and then do something with those responses: argue, defend, propose, compare, and analyze are some of the things we do with our responses to ideas. Each kind of assignment has a different purpose.

Generally speaking, arguments take two kinds of shapes: one is a shape that actively argues with its reader from the start, presenting its position and systematically defending against its opposition by marshalling evidence that will defeat an opposing viewpoint. This focuses on difference. One other popular shape starts from a position of unity and common ground, and then, as each element of common ground on a position is discussed, the writer’s position becomes clearer.